09 Nov Pity the Reader – An Interview with Suzanne McConnell

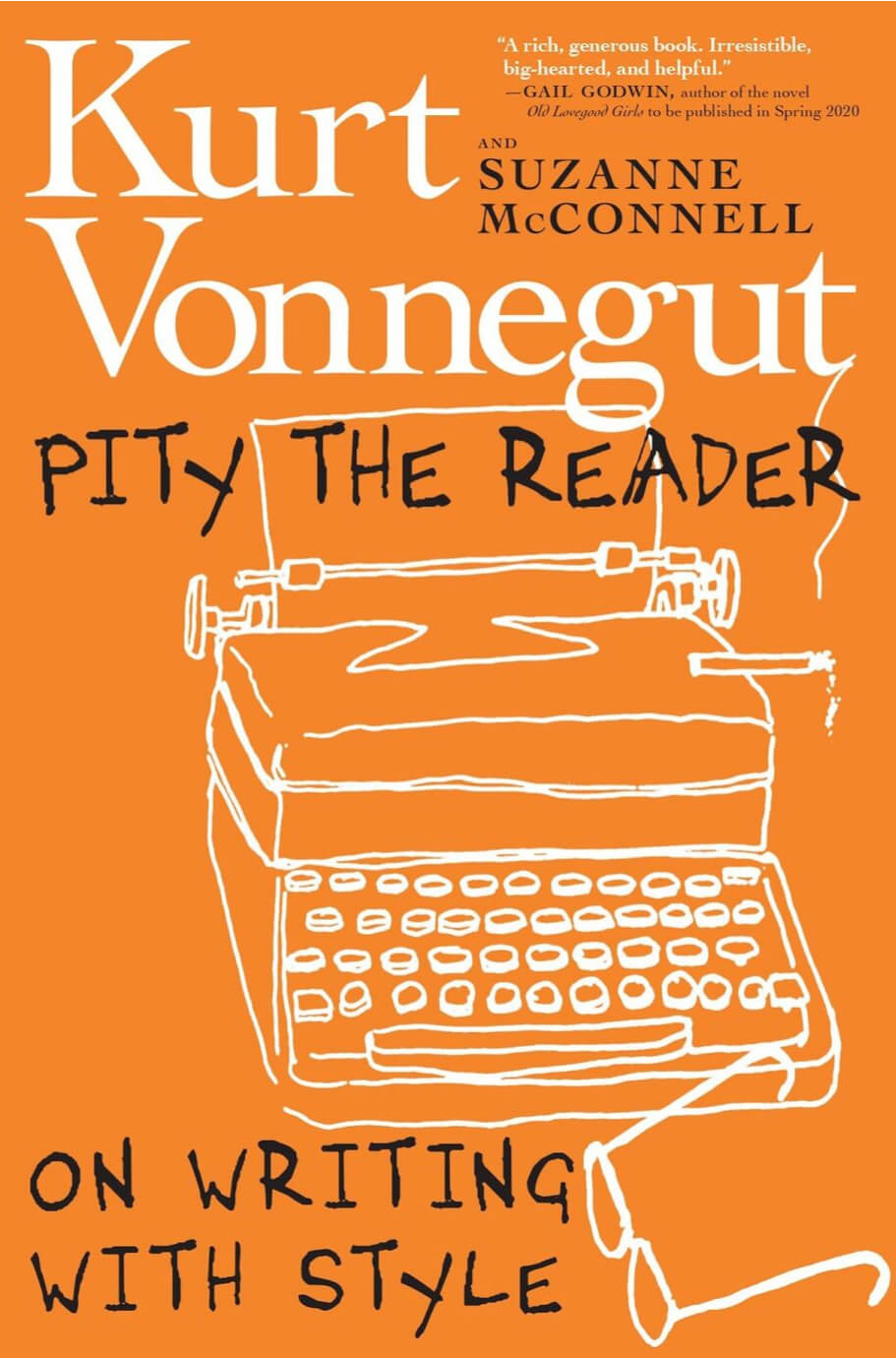

Ever wish you could become unstuck in time and wind up back in Iowa City during the 1960’s and enroll in one of Kurt Vonnegut’s classes at the Iowa Writers Workshop? If so, writer Suzanne McConnell is here to offer the next best thing. A former student of Vonnegut’s at Iowa, McConnell has mined Vonnegut’s many comments on writing fiction into the wonderful new book from Seven Stories Press, Pity the Reader: On Writing with Style by Kurt Vonnegut and Suzanne McConnell.

Ever wish you could become unstuck in time and wind up back in Iowa City during the 1960’s and enroll in one of Kurt Vonnegut’s classes at the Iowa Writers Workshop? If so, writer Suzanne McConnell is here to offer the next best thing. A former student of Vonnegut’s at Iowa, McConnell has mined Vonnegut’s many comments on writing fiction into the wonderful new book from Seven Stories Press, Pity the Reader: On Writing with Style by Kurt Vonnegut and Suzanne McConnell.

While Vonnegut’s name takes center stage, McConnell has done a masterful job of integrating Vonnegut’s collected wisdom with her own experience as a writer and teacher to create a highly readable guide to what it means to “write well.” A must-read for aspiring writers, it’s also a primer on making the arts a regular part of one’s life. Vonnegut and McConnell are inspiring teachers pointing the way toward writing, and living, with style.

McConnell shared her thoughts with The Daily Vonnegut.

Q: You have a long history as both student and friend of Kurt Vonnegut. In writing this book, did you discover anything new about his life and work? What surprised you?

McConnell: The most delightful and unique discovery I made (I’ve never seen it mentioned) was how frequently Kurt refers to music in his fiction.

The first task I set myself was to read and re-read most everything Kurt had published in his lifetime to look for recurring themes, fiction technique examples, dialogue about writing, and so on. I confined my references as much as I could to the work he knowingly approved of publishing – that is, while he was alive – and mainly to his novels, his primary focus as a writer. Anyhow, I found, to my wonder, that besides Kurt’s direct quotes about music so often seen now on the internet, allusions to music abound like a recurring refrain in all kinds of different ways in his fiction.

For example, the sweet sci-fi creatures in The Sirens of Titan, the Harmoniums: their vocabulary consists of sing-songing “Here I am, Here I am, Here I am,” and “So glad you are, So glad you are, So glad you are” back and forth to each other. Their name bespeaks “harmony.” Their planet Mercury sings. In his first novel, unpublished until after his death, the protagonist is a teen-aged boy who aspires to be a pianist. In Hocus Pocus, the narrator once hoped to be a musician and confesses that the most pleasurable part of his day occurs when he rings the carillon bells at the college where he teaches. A bland man has a secret life, in one of the short stories, as a terrific low-down dirty jazz pianist. And so on.

Music also shows up as black humor. In Galapagos, when burying the dead, people say, “Well, he wasn’t going to write Beethoven’s Fifth, anyway.” The ultimate in treachery wrought on the human spirit is often the sabotage or utter misuse of music. In Mother Night, a holocaust survivor remembers that one announcement in the camps – the call for the Sonderkommando, the escort to the gas chambers – was always crooned, like a lullaby. The character can’t forgive himself for being helplessly lulled by it. That chapter, that one description, for me depicts the complexity of the Holocaust’s horrors as little else I’ve read. Humanity’s capacity for the most egregious evil is coupled with humanity’s capacity for the sublime. For this character, the pull to the sublime for his survival shrouds the evil, and he’s forever shamed.

Q: When you knew him, did he talk about music?

McConnell: Not that I remember. At Iowa, Vance Bourjaily, another workshop teacher, would occasionally have musical gatherings in his studio at his farm. Anyone from the workshop who could play music was welcome, and the times I went (I play piano) Vonnegut brought his clarinet. So I knew he played music. Hs son Mark told me a few years ago that Kurt was an equally good piano player.

Discovering music throughout his work opened a door for me to approach advice about the craft of prose. Writers must attend to sound and rhythm in language, both on the page and for the ear. And those are the fundamentals of music. So I created chapters on prose as visual and prose as audial.

Another surprise: I think of Vonnegut’s language as being kind of flat. He says so himself. But upon close inspection, certain phrases are so spectacularly in tune, and his jokes so on target and well-timed, and he has such playful rhymes and colorful words. My chapter on Prose the Audial is stuffed with terrific examples of Kurt’s sensitivity to music in words. It became my own favorite chapter, at least of those on craft.

Things I already knew about Kurt became amplified, writing the book. I knew he came from a German-American background, but I didn’t know how intensely German. When I was in Indianapolis, Julia Whitehead, from the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, enabled me to see the house his architect father had designed for the family (from which they had to move during the Depression) and it was so German! I’ve spent a lot of time in Germany, because my husband, a visual artist, exhibits there. The house Kurt Sr. designed has decorative borders along the walls near the ceilings that are typically Bavarian. It’s a wonderfully substantial house.

I didn’t know that his mother was once engaged to a German nobleman or that her family owned a brewery, and I didn’t realize that the Vonnegut family was so prominent in Indianapolis, so that Kurt grew up surrounded by their contributions to society. His grandfather designed major public buildings; one—before World War II, named Das Deutsche Haus, now the Atheneum, still very much in use–also has blatantly German design features and a bar called the Rathskeller. These discoveries reinforced for me the irony of Kurt’s being a German-American fighting against and imprisoned by Germans, then bombed by Americans in Dresden.

It became much more apparent to me just how much he was working out psychologically through his fiction. Tracing his life, his non-fiction and reading the fiction with such close attention illuminated that.

Another amplification: how much Kurt learned to write fiction. It’s one thing to hear him say it, but it’s another to hold the drafts as evidence right in front of you. Seeing his drafts and rejections in the archives at the Lilly Library made his exhortations about the virtues of patience and learning the craft hit home.

One surprise was his incredible admiration for teachers. He had remarkable high school teachers. His teachers are models for characters throughout his books. He talks about writing as teaching and of writers as agents of change. His books are clearly aimed at persuading readers about useful ideas and examining society – like a good teacher. He describes what defines a good teacher extensively in Hocus Pocus and Galapagos. And he was a great teacher.

Q: What were your first impressions of Vonnegut at the Iowa Writers Workshop? Were you already familiar with his work?

McConnell: He was standing in the front of a Form of Fiction class with several other writers. I’d never heard of him. This lanky man, about 42, Kurt Vonnegut, was smoking from a long black cigarette holder. He looked humorous, slightly absurd, like he was putting on a pose and knew it. He immediately caught my eye and struck my funny bone.

The second time I remember seeing him was at a restaurant where I worked called The Steak-Out. All the fiction writing staff came in one night. Maybe it was their first social gathering, I don’t know. Vance Bourjaily was the lynchpin, because he lived in Iowa City and taught each semester, but all of the others were new to the Workshop – Nelson Algren and Richard Yates among them. For Kurt, his coming to Iowa was a big deal. He wasn’t famous. He was unsure of himself in a certain way, especially compared to other more mainstream writers. So I was trying to get their order and they were all talking, and Kurt paid no attention whatsoever, he was so interested in these other writers and their wives, and I remember just waiting, and finally Vance, who always had an eagle eye and knew what was going on in every part of a room, stopped everyone and said, “She needs to take the order.”

Q: You maintained a personal relationship with Vonnegut following your time as his student. Did the enormous success of Slaughterhouse-Five change him as a person and a writer?

McConnell: From one semester to the next we watched him gain fame. He went to New York because they put on his play Happy Birthday, Wanda June, and things began to happen for him. He got a three-book contract from Seymour Lawrence: Assurance that Slaughterhouse-Five would be published, promoted, and the two beyond that. Suddenly when you interacted, it wasn’t just with Kurt anymore; it was with him adorned in capital letters “Kurt Vonnegut.” We all became more self-conscious, and so did he.

Once in the early 80’s I was walking with him on the sidewalk going to lunch when Shirley MacLaine passed us and said cheerily, “Hello Kurt,” and he answered “Hi Shirley,” and he gave me a quick glance, his face fresh and holding a little wonder, and said “Did you see who that was?” He’d only recently become famous and jumped up a few rungs on the social ladder.

Watching his escalating fame from afar, as time went on, watching his agony over it, the choices he made, some of which were unfortunate, made me think a lot about fame and how it puts another cloak on you, and makes demands from complete strangers, and so I think he really valued those of his students who he kept in touch with who knew him from before. I was “grandfathered in,” as my editor/publisher Dan Simon, who became Kurt’s friend much later, said to me once. In his non-fiction, Kurt wrote how much he treasured those he knew from childhood and his young manhood coming up at GE. He notes most people feel similarly as they age, that’s certainly true for me, but it must be even truer if you’re famous. You’re assured that those people from early on were drawn to you yourself, not the capital letters.

I don’t feel equipped to talk about this subject adequately, actually. He stayed true to himself as a writer no matter what winds blew. In short, yes it changed him. And no, it did not.

Q: In reading Pity the Reader from start to finish, it becomes apparent how often Vonnegut wrote and spoke about “writing with style,” probably more so than other writers of his stature. Why do you think it was important to him to share his thoughts on writing?

Q: In reading Pity the Reader from start to finish, it becomes apparent how often Vonnegut wrote and spoke about “writing with style,” probably more so than other writers of his stature. Why do you think it was important to him to share his thoughts on writing?

McConnell: I think he hated the bullshit about writers springing out of God’s armpit or something like that. Because the craft of fiction was so hard won for him. And his learning the craft was tied up with necessity: supporting his family. He made statements about the requirement of talent and that good writers should just be left alone to grow. But he knew by experience that sheer talent is not nearly enough. Editors wrote back to him like teachers, with specific instructions about what and how to change a piece of work, especially once they’d accepted it. In her book The Brothers Vonnegut, Ginger Strand writes extensively about his early learning, his humble acceptance of editors’ advice, his persistence and patience. Which was considerable. Kurt was very practical. He was also incredibly empathetic with striving writers. He wanted them to know about the hard work–he admired hard workers–and he was by nature candid about such things.

Q: You attended the Iowa Writers Workshop in the mid-1960’s, which seems like a wonderful time to have been there.

McConnell: Yes and no. It was a really rich, intense time in every possible way. I’ll start with the negatives. It was very sexist. There were few women students, no women teachers. We didn’t have that word for it, and that’s interesting in retrospect, because when you don’t have the vocabulary for something, you can’t cite it easily or deal with it. You can tell anecdotes. “At the first party I went to, a guy told me seriously, ‘I don’t think women should write.’” Or, “The workshop guys got up a volleyball game and wouldn’t let any of the girls play.” But who do you tell these to? Other women. The workshop raised my consciousness more sharply than ever before in my life of the difference between how men and women were treated, perhaps because we had all arrived at the workshop on our merits, so the playing field itself should have been level. But it wasn’t. Women weren’t supported with assistantships, had to be far more outstanding to be taken seriously. One teacher of what we would now call creative non-fiction, Richard Geyman, brought a bottle of Bourbon to sip in class and always said “Here she comes,” whenever I, the only woman in the class, entered the room. I saw him in a store in town one day and asked him about a paper of mine he’d not turned back, and he looked quite blank. That night about 3 AM he phoned, drunk, and said in a husky, drunken voice, “Suzanne, come over. Take a cab.” About ten years later I told Kurt about that. He laughed. It was funny, even endearing, poor guy, but I wanted to be taken seriously.

In the seventies, a decade later, I wrote a long letter to Vance Bourjaily, spilling my heart out about the treatment of women at the workshop then, and he replied that there was no way he could answer my letter in kind but that some of the more obvious injustices had been righted. He concluded, “But I’ll still always think of you as the pretty-faced girl.”

One of my strongest memories of Iowa City isn’t about the workshop. In celebration of its 50th anniversary in the eighties, the Writers’ Workshop requested memoirs for a commemorative booklet. I was in Germany at the time with my husband, and I kept trying to write lovely memories, but what kept coming up was this dark wound. Three students, all of whom I knew, died in one week where I lived, next door to the Vonneguts. Jane Vonnegut hurt her knee badly in the days following, when I led her down a plank, in place of stairs, to a basement room. Vonnegut was furious when he discovered such living conditions. Recently I revised the memoir slightly for a larger audience, clarifying names and places, and wrote an afterword in a spill of words that flew out of my pen while at a Pain Quotidian. “Black’s Gaslight Village” was published in March, 2020, in the Brooklyn Rail on-line and in print. (Read here.)

Another issue: People who graduated from Iowa who became teachers learned that they needed to actually teach more than ours had. A lot of the teachers got jobs at the Workshop then because they needed a job, like Richard Gehman, and the old boys’ system helped them get a job. Nelson Algren was a terrible teacher. He was gambling all night, he thought it was ridiculous that we were there at the workshop. Our writer-teachers, even the best like Vonnegut, didn’t guide or set up a supportive atmosphere. If my students started to rip into each other, I stopped them; I set up rules ahead of time, and so did all the others’ teaching writing at Hunter and elsewhere. But at Iowa at that time it was a free for all, and people could be vicious and competitive. So that was a negative. You gained a thick skin. You learned to hold on for dear life.

I must say, though, that what I’m citing as negatives spurred growth. My favorite made-up Bokonoist word in Cat’s Cradle is “wrang-wrang.” These were all wrang-wrangs for me: they led me not to follow the example, or to try to change things, or to realize what it means to be mortal.

The positives were just as intense. It was like going to an elite art colony for two and a half years. It was the Sixties. We were in Quonset huts the first year. They were cold. They were ramshackle. But we didn’t care about that stuff; we just cared about our writing. Writing was almost like a religion. The bar was high. Being surrounded by fierce ambition, intelligence and talent from both students and faculty was heady stuff.

I went back for the 75th anniversary. There’s now a beautiful workshop library. I didn’t like it. The atmosphere seemed too precious, too aware of itself. Reverse snobbery, I suppose.

Another wonderful thing: the relationship between faculty and students was fluid. We socialized. I was on the young side. The lines blurred even more if you were older. Iowa City is small. We encountered each other on sidewalks, the bars, in stores. Once Kurt told us dreamily that he’d been to a movie at the local theatre, “A Man and A Woman,” about the courage to love. I made a beeline to see it, easy enough, the only one in town. Kurt and Jane threw parties, the Donosos gave dinner parties. Not everyone was included in everything (I only heard about the Donosos’ dinners), there were too many of us and people naturally inclined towards those with whom there was affinity. I invited Kurt and Jane to dinner in my shabby graduate student apartment and held at least one party there. I recall Dick Yates on my couch complaining, “Can’t we ever talk about something else besides the business of writing?” Often when something wonderful happened, we celebrated. When Mary Kathleen O’Donnell, Kurt’s student and my friend, got a story accepted in the Atlantic Monthly, the Bourjaillys threw a spontaneous celebration and everybody who knew her went to their farm for beer. She used to ride horses with Tina Bourjaily. You learned a lot about how writers lived from being around them. They liked to have fun, and they were dedicated to their work. That kind of intensity was stupendous.

Here’s a story, I don’t recall if it’s in the book. Vonnegut was insecure about his lack of an English literature background. So in this Form of Fiction class, a student makes a reference to Keats. Kurt looks up, perplexed, and asks, “Who’s Keats?” And there’s a hush. Then someone says, “You know, Keats, the English poet?” Kurt threw the book against the wall and walked out of the room. We all started laughing. Then he came back, midst our laughter. In front of class again, he said, “I thought it was a student I didn’t know.”

Vonnegut was so human, as a teacher. He had a certain distance of course, but he did not pretend impartiality or superior knowledge if he didn’t possess it. I presented a story in class about a young woman working in a nursing home, and in one scene she’s with an old man, trying to wash his back. Vonnegut got furious that she was taking away the man’s sense of self-empowerment by trying to help him. It was the first time in my life it was suggested to me that helping someone takes away his or her agency. Another day we were complaining about the flatness of Iowa, the barely rolling hills, and he looked up in his understated way and said, “People have wars over land like this.”

Q: In what ways did Vonnegut most strongly influence your own work as a writer and teacher?

McConnell: I was drawn to him among the other faculty because I had no background in English literature, either. He was responding to trauma and what he was angry about, which is what I was doing. That helped me combat my insecurity about not being scholarly. He was down-to-earth, refreshingly more human and sharing of himself – not without reserve, I don’t mean that – than any teacher I’d ever had.

In 2004, he wrote to me, “About your stories: Saul Steinberg said there are two kinds of artists, those who respond to the history of their art, and those who respond to life itself. You are the second kind. Are you ever!”

In terms of style, he didn’t influence me. Most of my fiction is realistic. The novel I wrote was lyrical, the California landscape almost a character itself. Kurt wasn’t a realistic, descriptive writer. But I have flash fiction stories that are wacky and black-humored like his. He totally influenced me as a model of commitment to writing, to humanistic values, and the urgent worth of writing.

Q: Do you have a particular favorite among Vonnegut’s works?

McConnell: People always ask that question, and they expect me to say Slaughterhouse Five. I love Slaughterhouse-Five, but I don’t really like the sci-fi sections, and Billy Pilgrim is pale as a character. Who could like him? He’s damaged. He’s a washrag. That’s the point. I cherish the minor characters including Billy in terms of how their war experiences affect them. It’s Kurt’s message and the unique way he writes and portrays war and its issues that I admire. But I have all kinds of favorites. I love the wild playfulness of Breakfast of Champions. I taught Cat’s Cradle several times and adore the humor and language. Mother Night, Galapagos are stupendous. The short stories in Welcome to the Monkey House. Etc. No orphans in my cadre of what’s to like.

Q: Pity the Reader is about writing with style, but it’s more than that, as it also provides advice on making the arts a part of one’s life, whether it’s writing, painting, dancing, etc, and whether or not one seeks to do it professionally or even has any talent. In writing this book, was it your intention to emphasize the importance of the arts?

McConnell: I think you picked up on that. It wasn’t intentional. I mean, I didn’t plan that or even know that I did that! Let me tell you its history.

When Dan Wakefield proposed that I write this book, he and the Vonnegut Trust told me that it was to be aimed at writers and teachers, and Vonnegut fans of course. My working title was Vonnegut’s Pearls: Kurt Vonnegut’s Advice on Writing for Writers, Teachers, and Everyone Else by Suzanne McConnell. My publisher/editor came up with the zippier title. So my own aim was to reach ‘everyone else’ too. I believe Kurt’s advice on writing and the examples from his life’s writing journey apply to any artist of any kind, or to any person striving to accomplish anything.

I wrote the book the way I taught, I discovered after a while – the way Kurt’s character Mary Hepburn in Galapagos teaches – bringing in whatever is useful to the subject you’re teaching. So it’s part biography, part writing advice, part memoir. Whatever came to mind pertinent to the point.

People are surprised that the book is not just about writing. My sister, matriarch of a sprawling family, a piano and guitar teacher, exclaimed upon beginning it, “This isn’t a book for writers. This is a book for anyone.” My niece, a therapist, called the other day and said, “I just used your book for a client,” a nurse uncomfortable being a nurse. She applied Kurt’s writing advice about caring for your subject as career counsel. I’ve gotten many such responses from strangers.

But if Pity does emphasize the importance of the arts, perhaps it’s because Kurt did. I agree with him that the creative process “makes your soul grow.” You get big hints, often revealing more than you consciously know, when making art of any kind, about what you feel and who you are. And as audience, responding to the arts can do that too, beside bringing joy.

Also I live in New York City which is filled with art and artists of every stripe. Most gravitated here from somewhere else because of that. People discuss and go to theatre, art openings, music performances, museum exhibitions. It’s part of life here. The lifeblood.

Q: Why do you think Vonnegut continues to be relevant in 2020, more than 40 years since he first came to prominence with Slaughterhouse-Five?

McConnell: His concerns are timeless. Some have become more relevant. Like Deadeye Dick. Now we have school shootings and gun control arguments, and this novel is about a kid who doesn’t mean to shoot anybody. It’s an accident; it’s just the damn gun that is the source of the problem. Galapagos is about the environment. Kurt said it was his favorite book. And I think he said that because the demise of the planet is the most important question humankind faces and he was trying to deal with that. Over and over in it he cites the failure of the human brain. Galapagos is perhaps as impactful in its dire warnings as scientific reports. And a lot more entertaining. And even Player Piano, his first novel, about mechanization. A title that sports a musical instrument, one Kurt loved, turned into a mechanical thing programmed to play itself. No human hand or creativity necessary. What’s happening with our technology now goes far beyond Kurt’s experience at GE of mechanization. It’s revolutionizing everything, our daily lives. We don’t even turn on our own faucets in public places anymore. We don’t know where we are going in this digital revolution, but it certainly erodes the use of tactile skills and face-to-face personal dynamics. (At this Coronavirus time, however, what could be more useful than our digital technology? It’s saving us!) Or take prisons and the justice system. In Jailbird, he’s got the whole story of Sacco and Vanzetti. You discover it’s not old news. Injustice is forever, and our present criminal justice system is a racist disaster. Also, he’s just funny. He’s provocative and entertaining. Plus Vonnegut’s books are taught in school, and that, as he himself said, perpetuates sales and interest.

Q: In Pity the Reader, I sensed Vonnegut becoming a stronger voice through the progression of the chapters. You get the sense of working toward something, some culminating lesson.

McConnell: If so, again that was unconscious. Maybe if I describe the process, the answer will reveal itself. What carried me through the framework of the entire book was Kurt’s fundamental piece of advice. I spotted “How to Write with Style” in The New York Times (now the endpapers in Pity) when it was first printed in the early 80’s and used it in every writing class I taught after that. His first advice for anyone writing anything is to write about what you care about and what you in your heart think others should care about. His own writing life follows that trajectory.

Kurt’s early aim was to deal with his experiences in the crucible of the bombing of Dresden, and war itself. Americans didn’t know about it widely. He felt deeply that they ought to. Chapter 2 through 8 derives from his journey writing what became Slaughterhouse-Five. Initially, in draft, I divided the book into sections. This one was called “The Prime Mover.”

Kurt’s angst and the risks he took to write Slaughterhouse-Five led to the question: why write, if it’s so damn hard? My answers became the next two sections “The Worth of Writing to the Self” (Chapters 9-11) and “The Worth of Writing to Society” (Chapters 12-14). Mind you, everything in Pity also emerged from the material I’d initially underlined from Kurt’s books and categorized loosely in digital form, to use as needed.

I’m a writer, I’m old, and I know something about the twists and turns that you come upon on the journey. So as I began the chapters about the craft of fiction, I found myself thinking about all the emotional and attitudinal demands writing requires, and by extension any art, or difficult self-starting task. The first question is, beyond whether you feel the passion to achieve something: do you have the talent? The Paris Review interviewer asks Kurt that question, and also whether writing can be taught. Answering those kinds of things became “Section Four: Tools of the Trade: Approaches” (chapters 16-22).

One reason I was concerned is from my teaching experiences. I had a student in my private classes who worked on Wall Street, and she got very excited about writing, so she saved money and quit her job to do it full-time, and then she had a hell of a time. She didn’t know how to be a writer. She didn’t know that you don’t have to write all day, for example. She didn’t know much about solitude, self-motivation, failure, and how you keep yourself going; these aren’t easy, and those kinds of things are half the struggle. These take time to learn, the kind of thing being at Iowa helped you learn, with all those writers as models and time to try it out for yourself. I failed her by encouraging her, not fully realizing how long it took me to learn those mental habits, and not warning her. So I thought people needed advice on how important other aspects are, besides craft itself.

Craft (Section Five: Tools of the Trade: Nut and Bolts, 23-31) came next. Those chapters may appeal mainly to writers and teachers of writing but are entertaining and informative enough to draw in all readers as well. The paperback (coming out in Nov. 2020) will include an appendix, “Practices,” for people and students to try their hand at Vonnegut-esque writing exercises.

The final section may be key to your sense of Pity’s striving toward some ultimate thing. The lack of section divisions or titles in the published book may obscure the sense that those chapters are collectively about how to live. But that’s what I originally called it: Section Six: How to Live as a Writer (Chapters 32-37). I struggled over including it. The last summer I worked on the book, I woke up one night with an epiphany: “I don’t need this section! I’m done!” Two days later, I returned to slogging it out.

Because how to live as a writer also means how to live as a human being. I’d found tons from Kurt’s non-fiction and illustrations in his fiction on various topics of living well. “The main business of humanity is to do a good job of being human beings…” the main character in Player Piano says. Perhaps that’s the book’s heading towards something. This larger message.

My early inkling to include such a topic was reinforced at an AWP (Associated Writing Programs) conference in 2014 (I presented a panel on “Vonnegut’s Legacy: Writing about War and Other Debacles of the Human Condition”). I spotted a panel about managing life while writing. And I thought I’d check out who showed up and what they said. To my amazement, the huge room was packed. People were sitting on the floor, spilling out the door. They were hungry to know how to manage to pay the bills, have a spouse, children, a full life, and write too. Every artist wonders. Every person wonders how to live well.

Vonnegut’s main advice is about life, and about how to be human, and humanitarian, and all of his books are based on this idea. Pity concludes with a chapter called “Better Together or Community,” pro and con. Right now, with the pandemic of the coronavirus uniting the entire world in separation, a Vonnegut-esque turn of events if there ever was one, his remarks about how comforting community is and how in times of duress people have always joined in common cause, makes a powerful appeal. For all Vonnegut’s discomfort and criticism of life on earth, he also revered life. He just wanted it to be better. So Pity ends with Vonnegut invitations, one from Cat’s Cradle in the 60’s and another from unpublished poems from 2005, to behold the blessing of being a part of life itself.

A photo excised from the final manuscript is a Times photographers’ capturing an old man sitting on his bed in his Sarajevo bombed-out room full of debris, bent over a small record player, listening to music. That’s the spirit of Vonnegut I wanted to convey. It’s an urgent message. It’s for everyone.

No Comments