Kurt Vonnegut’s literary reputation in the United States has been well-documented, but little has been written about his impact in the Soviet Union during the years of the Cold War. Sarah D. Phillips is set on changing that. Phillips, a professor of anthropology at Indiana University, has done valuable research on Vonnegut’s presence and popularity in the Soviet Union. Her lecture, “American Literary and Cultural Diplomacy during the Cold War: Kurt Vonnegut in the Soviet Union” is available on YouTube.

Kurt Vonnegut’s literary reputation in the United States has been well-documented, but little has been written about his impact in the Soviet Union during the years of the Cold War. Sarah D. Phillips is set on changing that. Phillips, a professor of anthropology at Indiana University, has done valuable research on Vonnegut’s presence and popularity in the Soviet Union. Her lecture, “American Literary and Cultural Diplomacy during the Cold War: Kurt Vonnegut in the Soviet Union” is available on YouTube.

Dr. Phillips recently shared her thoughts with The Daily Vonnegut.

The Daily Vonnegut: What inspired you to begin researching Kurt Vonnegut’s literary presence in the Soviet Union?

Sarah D. Phillips: It all started with a middle-of-the-night rogue tour of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis about seven years ago! After a Maceo Parker concert at the Indianapolis Jazzfest, my husband William Morris and I stopped in to eat at an adjecent bar. We happened to be seated near Chris LaFave, a curator at the nearby KV museum. We got to talking with Chris and he offered us an exclusive 1am tour of the museum, which of course we couldn’t resist. William and I were blown away by the museum’s rich collections and have been Vonnegut devotees ever since!

The project to research Vonnegut’s “Soviet chapter” really got started in 2017 with my participation …in “Salo University” at the Indiana University-Bloomington Arts and Humanities Council. Salo University was a Public Humanities Project bringing together a “justice league” of professors from different departments to read Vonnegut’s first six novels and blog about them from our own disciplinary perspectives. The goal was to think collectively about how and why Vonnegut’s work still matters today. It was a terrifically fun project and there’s a great website where readers of the Daily Vonnegut can learn all about the project and read the blogs.

Anyway, as I read Vonnegut’s first six novels and tried to contextualize them from an anthropologist’s perspective, I learned so many amazing things about Vonnegut and his work. I was intrigued to learn that his novels and stories had been hugely popular in the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. Since my geographical specialization is Russia, Ukraine, and Eastern Europe, I was intrigued! I kept scratching away to see what I could learn about Vonnegut’s popularity with Soviet readers.

The Daily Vonnegut: Donald Fiene and Rita Rait are two important figures in the story. Tell us about them. (Note: Rita Rait was also known as Raisa Rait-Kovaleva).

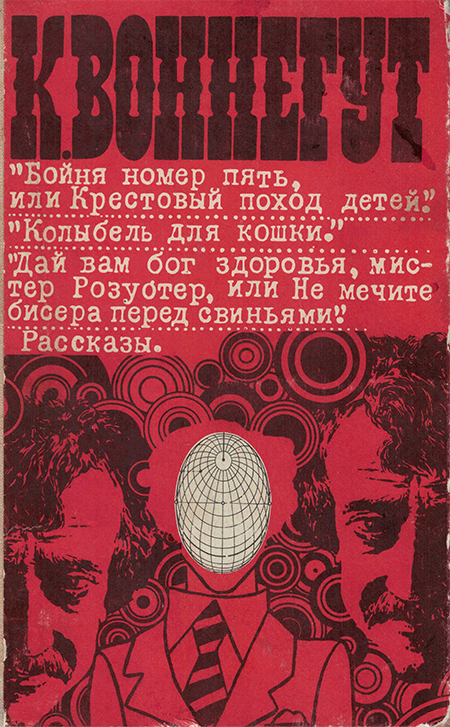

Sarah D. Phillips: Indeed, Vonnegut had Donald Fiene to thank for his popularity in the Soviet Union. Fiene, who earned his PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures at IU, was obsessed with Vonnegut’s “Soviet chapter,” and even helped orchestrate it! One of Fiene’s major projects as a young scholar in the early 1960s was to track J.D. Salinger’s popularity in the Soviet Union. For that endeavor he wrote a letter in 1961 to the translator Rita Rait, who had translated Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye into Russian to great acclaim in 1957. The two struck up a friendship that lasted for two decades. Fiene visited the Soviet Union for research and always supplied Rita Rait with new books from the West. During a visit to Moscow in 1966 he gave her a copy of Cat’s Cradle, and the rest, as they say, was history. Rait first translated Cat’s Cradle and Slaughterhouse Five, both of which appeared in Russian in 1970, and she went on to translate Happy Birthday, Wanda June (1973), Breakfast of Champions (1975), God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1978), and many of Vonnegut’s short stories during the 1970s and into the 1980s.

Rita Rait was a terrifically important translator of Western literature for Soviet readers—in addition to Vonnegut and Salinger she translated Faulkner, Hemingway, Twain, Robert Burns, and Graham Greene, among others. She translated not only American and British literature, but from the French and German, too: Kafka, Sarraute, and Boll. By the time she started translating Vonnegut’s books in the late 1960s, she was 70 years old and had long ago established herself as a grande dame of Soviet translation. Becoming “Vonnegut’s translator” really gave her career a kind of second wind.

So, it was Donald Fiene who introduced Rita Rait to Vonnegut’s writing, and he also helped arrange an in-person meeting for Rait and Vonnegut in 1972 in Paris. Rait was spending a month working with the writer Nathalie Sarraute and researching her own book on the French Resistance writer Boris Vilde. Thanks to Fiene’s intervention, Vonnegut stopped off in Paris en route from London to meet Rita Rait. They spent a lovely couple of days in Paris and Vonnegut later visited Rait in the Soviet Union twice—in Moscow in 1974, and in Leningrad in 1977. The three colleagues—Fiene, Rait, and Vonnegut—all kept up active correspondence with one another through the 1970s and 1980s (Rait died in 1989), and it has been terrific fun tracking down and reading their letters. I found them in the Vonnegut and Fiene archives at the Lilly Library at IU Bloomington, the Donald M. Fiene papers at the Ekstrom Library at the University of Louisville, and in the Russian State Archives of Literature and Art in Moscow, where some of Rita Rait’s papers are housed.

As my research progressed, I just kept following the breadcrumbs Don Fiene left behind. In a way I am continuing and expanding a project Fiene started years ago about Vonnegut’s reception in the USSR. I amassed lots of new sources, carried out archival research in the US and Russia, and did interviews with Vonnegut fans in Russia and Ukraine. I am working on putting all this together into a book manuscript. I’m sorry I never met Don Fiene, who passed away in 2013.

The Daily Vonnegut: In Wampeters, Foma, and Granfalloons, Vonnegut included an essay, “Invite Rita Rait to America’, originally published in The New York Review of Books. Did Rita Rait ever make such a visit?

Sarah D. Phillips: Although some sources state incorrectly that Rita Rait did visit the United States, unfortunately she never did. Donald Fiene and Vonnegut tried twice to arrange a big US university lecture tour for her, but the Soviet authorities never granted Rait an exit visa for the US. Over the years she made extended work trips to the UK and France, and to Prague, but the Soviets never allowed her to visit the US.

The Daily Vonnegut: What do you think accounts for Vonnegut’s popularity with Soviet readers during the Cold War?

Sarah D. Phillips: There are so many reasons readers in the Soviet Union during the Cold War connected with Vonnegut! Soviet readers loved Vonnegut for many of the same reasons American readers of the late 1960s and the 1970s did. Like in the US, many of Vonnegut’s biggest fans in the Soviet Union were young people—teenagers and university students. The historian Donald Raleigh calls this generation the “Soviet baby boomers” and wrote a terrific book of the same title. These readers loved Vonnegut’s unique writing style: his humor and sarcasm. The post-war generation was also fairly obsessed with anything American—they wanted to know all they could about American culture, and Vonnegut was a terrific cultural guide. Reading Vonnegut was “cool,” and these young readers incorporated “Vonnegutisms” (concepts like karass, duprass, grandfalloons, the tenets of Bokononism, etc.) into their speech, almost like a secret code shared among devotees of Vonnegut. And some readers gravitated to Vonnegut because his writing contains elements of science fiction, which was extremely popular in the Soviet Union at the time.

But Vonnegut struck a deeper chord with readers, too. His writing appeared in translation in the Soviet Union during the period of “Stagnation” under Brezhnev, after Khrushchev’s “Thaw,” which had shone light on the excesses of Stalin’s terror and the Soviet people were trying to come to terms with major “dark spots” of Soviet history. The Second World War was one of these “dark spots.” Works of Soviet writers casting doubt on official histories of the glorious Soviet victories of the “Great Patriotic War” (as WWII was called in the USSR) were published, and the appearance of Rait’s translation of Slaughterhouse Five in 1970 coincided with this trend. For Soviet readers coming to terms with the unfathomable loss of life the Soviet Union suffered during Stalin’s purges, and during WWII, Vonnegut’s unusual “war novel,” his portrayal of war as brutal, haphazard, and even senseless, was a revelation. His description of the Second World War as a “children’s crusade” was a gut-punch to the established Soviet narrative and lined up with other critiques that were emerging in the Soviet Union.

Soviet readers also connected with Vonnegut’s unlikely “heroes,” the hapless Billy Pilgrims and Elliott Rosewaters. As one Vonnegut devotee named Natalia Shulga that I interviewed put it (I’m paraphrasing here): “Vonnegut’s heroes look quite stupid. They are just like us—they are decent people trying to survive in an indecent world.” I interviewed lots of Cold War Soviet readers who said they had been able to “see themselves” in Vonnegut’s characters. A lot of people I interviewed in Russia and Ukraine said they loved Vonnegut for his “humanism.”

And this brings me to another reason Soviet readers loved Vonnegut: his books helped them contemplate and confront a slew of moral and existential questions: the role of science and technology in society, the excesses of crass consumer capitalism, the nature of ideology in fomenting hatred and evil, the worst sides of human nature, the nature of free will, and much more. A terrific scholar named Yana Skorobogatov wrote a lot about this in her 2012 master’s thesis about Vonnegut in the USSR—she noted that “Vonnegut storylines, characters, and overall philosophy inspired his Russian readers…to think about their past, present, and future in new and bold ways.” That’s exactly right!

The Daily Vonnegut: How did Vonnegut’s war experience influence how Soviet authorities viewed him and his work?

Sarah D. Phillips: His experience as an American soldier in WWII—Vonnegut was a POW during the Dresden firestorm who barely escaped with his life under “friendly” fire—gave Vonnegut enormous credibility with Soviet authorities. I think that is a major reason he was a “sanctioned” foreign author. His unusual war experience was kind of a double-edged sword, though. The authorities could lean on it to lambast the crassness of the Allied forces’ bombing of Dresden, a non-strategic city they had no business targeting. On the other hand, Slaughterhouse Five drove home to Soviet readers—in a context where they were exposed only to the story of Soviet sacrifice and victory in the war— the somewhat novel notion that citizens of other countries had also fought and died in the war. That sort of disrupted the established narrative that the Soviet Union single-handedly won the war.

The Daily Vonnegut: Have you read any of the Russian translations of Vonnegut’s work. If so, what did you think of them?

I have! I have focused on Rita Rait’s translations, at times reading her Russian translations in parallel with Vonnegut’s originals in English. It’s a fascinating exercise to try to get inside the mind and practice of a translator. There’s a joke that goes around, based on something Gore Vidal supposedly once said: “Vonnegut writes better in Russian.” Meaning, of course, that Rait’s translations are better than the original works. I don’t think that’s true, but her translations are great. The great editor Aleksandr Tvardovskii once told Rait that she’d translated Slaughterhouse Five “jauntily,” and I think that’s a great description.

Rita Rait tried to fully inhabit the text she was translating, to get inside the minds and life worlds of the characters. You can imagine how hard this was when she had never been to the US! Sometimes she got really creative in rendering American cultural-specific objects and situations for readers unfamiliar with the context. She substituted “hockey stick” for “baseball bat,” that sort of thing. One of her greatest triumphs was substituting “unbuttoned mink” for “wide-open beaver” in Breakfast of Champions. That just works perfectly in the Russian context. Some of Rait’s translations were heavily censored—most of the sexual material was censored out of Breakfast of Champions, for example. In some re-issues of the books in Russia, all that has been added back in.

The Daily Vonnegut: You’ve conducted archival research in Russia. Most Americans have a limited view of life in Russia. Are there any thoughts you’d like to share about your experiences there?

Sarah D. Phillips: I think many Americans don’t realize what a diverse country Russia is. It’s an absolutely huge country, nearly twice the size of the US. Although most of the population is concentrated in western Russia (especially Moscow and Saint Petersburg), European Russia only makes up about one-quarter of Russia’s total land mass. Three-fourths of Russia is in Asia. People living in Russia come from many diverse ethnic backgrounds, and the country has 35 official languages. Western media tends to focus on Russia’s two big cities, which leaves out so much of the country.

The Daily Vonnegut: Is Vonnegut still popular in current-day Russia?

Sarah D. Phillips: People still read his books, but I don’t think they are as popular as they were in the 1970s and early 1980s. Access to literature is just so open now, choices for what to read abound! There is a publishing house in Moscow, AST, that recently re-published seven of Vonnegut’s novels in Russian in its “Exclusive Classics” series. You see these books prominently displayed in any big bookstore in Russian cities. The market is definitely still there. And the Babylon Library Press in Ukraine recently published beautiful new Ukrainian translations of Slaughterhouse Five, Slapstick, and Breakfast of Champions. I was so delighted in 2018 when I visited Kyiv, the capital city of Ukraine, and my friend’s teenage daughter was reading Slaughterhouse Five in Ukrainian on the recommendation of her school friends. Viva Vonnegut!

The Daily Vonnegut: Were you a Vonnegut reader prior to embarking on your research? Do you have a favorite among his novels?

Sarah D. Phillips: Before I was invited to be a part of the Public Humanities project I mentioned earlier, I’ll admit I had only read one of two of Vonnegut’s books. The first Vonnegut novel I ever read was Player Piano, and it is still my favorite. It was the first book he published, and a lot of experts don’t see Player Piano as fully representing the style and voice that Vonnegut perfected in his subsequent work. But the subject matter—labor rights, class and racial inequalities, long-term effects of the “technological revolution,” and fears about the mechanization of all parts of life, really moves me. I also really love Slaughterhouse Five and Sirens of Titan, but Player Piano will always be my first and favorite Vonnegut book.

The Daily Vonnegut: Do you have any future plans for additional work on Vonnegut and the USSR?

Sarah D. Phillips: My main goal for now is to shape all the research I have done so far into a book about Kurt Vonnegut and the USSR. The book will have chapters on Rita Rait’s translations in the political context of the Cold War (what she had to change and leave out, for example), stories about Soviet readers who loved Vonnegut and why, information on how literary critics received Vonnegut, and the relationships Vonnegut formed with Soviet émigré and dissident writers like Sergei Dovlatov. And of course, there will be many fun stories about Vonnegut’s trips to the Soviet Union and his friendship with Rita Rait. I want the book to be accessible for a general readership, and I hope it will appeal to a wide swath of readers, including Vonnegut fans and Soviet history buffs. It’s a terrifically fun book to write!

Dr. Sarah D. Phillips is Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Robert F. Byrnes Russian and East European Institute at Indiana University (IU). A cultural and medical anthropologist by training, at IU Phillips has taught courses on Culture, Health & Illness; Anthropology of Russia and East Europe; and Post-socialist Gender Formations since 2004. She has published two books about Women’s Social Activism in Ukraine and the Ukrainian Disability Rights Movement. Phillips also did research on gender, HIV, and drug use in Ukraine. Her current project on Kurt Vonnegut’s resonance in the Soviet Union during the Cold War is her first foray into literary historical research, and she is loving every minute of it.